An unexpected journey from bitcoin to Christ

The following article describes how my interest in bitcoin set off a chain reaction in the development of my thoughts over the past few years. The journey described is quite personal, but I’ve decided to share it with the hope that it may help someone begin to see and navigate some possibly unexpected connections between important subjects—bitcoin, time preference, beauty, philosophy, and Jesus of Nazareth. I believe the connections are bidirectional, and capable of leading truth-seekers who love bitcoin to love Christ, and those who love Christ to appreciate bitcoin.

Chapter 1: A secular culture and finding bitcoin

My parents brought me to church on Sundays as a child, which I now look back on as a valuable experience in my early development, although at the time I didn’t understand it and viewed it as a chore. As I approached my teenage years, my parents gave me the option to choose whether I wanted to continue attending, and I decided to go less often, and eventually stopped going entirely. My life was subsequently absorbed into my local school system, in which the teachers emphasized a secular view of science and critiqued religious fundamentalist perspectives. Many of my peers and I began to see religion as a primitive, regrettable institution responsible for leading people astray from the truth.

This approximate perspective held for many years. Simultaneously, I grew toward adulthood, and began thinking more about my future, considering how to build up savings so that I could become self-sufficient. When I grasped the phenomenon of inflation, I remember recoiling and thinking that it seemed inherently unfair and disordered, that the money I was paid for my work would be expected to decline in value over time. I intuited that this arrangement incentivizes spending now rather than saving for later (when the money would be worth less), and people who want to build savings to reduce future uncertainty in their lives were at a disadvantage.

Savers must turn to other mechanisms that are more likely to hold value across time—this sparked my interest in gold, and its reliably lower inflation rate of about 1.5% per year. A few years later, I discovered how bitcoin manages to offer savers a verifiably fixed supply, and therefore no inflation at all, a concept realistically unavailable to humanity previously. By extension, it also implied that bitcoin’s creation was the first time in human history that the act of saving became relieved of the illness of inflation. This solved my personal dilemma, and excited me about bitcoin’s future adoption and the wealth it would provide to early supporters. But it also began to raise questions about the broader implications of this new development upon humanity.

Chapter 2: Time preference

Not too long after I became enthralled by bitcoin, I also began to discover the Austrian School of Economics, due to the substantial overlap in ideals. Writings from people such as Saifedean Ammous helped me understand more about the concept of time preference, which provided words to explain the observations I had subconsciously understood for many years.

Time preference builds upon the basics of the human condition. We are mortal and the future is uncertain. This means we would prefer to have desirable things in the present rather than a later date (which we may no longer be around to experience), all else being equal. However, we have also managed to notice that typically, all else is not equal—by choosing to have things in the future, we can allow for their further development over time, such that we (or our descendants) end up reaping a greater reward down the road than what we would have had by harvesting in the present. Therefore, a person can have a time preference that is higher (more preference for the present) or lower (less relative preference for the present).

A higher time preference tends to result from a higher degree of uncertainty about the future, such as individuals living in poverty, bad health, or danger. These conditions bend a society’s culture toward instant gratification, and a decreased willingness to make sacrifices in the present for possible future benefits which may never be experienced before death. Meanwhile, a lower time preference is more likely to be found among those who perceive a lower degree of uncertainty in their future, such as individuals with good prospects of wealth, health and security. These blessings build optimism and confidence about the coming years of life, and foster a greater willingness to make sacrifices in the present for extra benefits in those times ahead. The result is a culture that leans toward saving and investment rather than consumption.

It became clear to me that one’s behavior in the world is affected by their time preference, and that a factor of one’s time preference is the level of uncertainty surrounding their savings and wealth. Furthermore, uncertainty surrounding one’s wealth is dependent on the form in which it exists—the tool that is chosen to store wealth. If someone holds an asset that suffers from inflation, their behavior will (perhaps slightly and subconsciously) become more oriented toward the immediate, at the cost of the future. So too if someone holds stocks and is concerned about an impending economic downturn, or holds real estate and must pay for ongoing upkeep and property taxes.

The tool for storing wealth that would enable the lowest time preference, and thus incentivize investment in the future to the greatest extent, would be the tool that minimizes uncertainty for the holder as much as possible. Ideally, this tool would have no expected deterioration in value due to things such storage expenses, perpetual taxes, or inflation (otherwise the holder would incur more and more uncertainty as time passes), and would offer robust protection from risks such as theft or physical damage. The best tool became bitcoin when it was invented, and thus a new hope for lowering the time preference of mankind was conceived.

Chapter 3: Objective beauty

My education continued from Ammous and others, who helped me understand the deeper implications of time preference within society. A society of higher time preference ends up leading toward vice and ugliness, because pleasure in the moment is prioritized, while the sacrifices necessary for virtue and quality craftsmanship are less likely to be made. Conversely, a society of lower time preference encourages such sacrifices in the interest of beauty, social harmony and long-term fulfillment.

For years I had grappled with frustrations regarding the direction of the culture around me, having noticed the creeping growth of pessimism and party-culture debauchery, alongside a decline in quality across the board—products, services, food, art, music, shows and movies, architecture, clothing styles, the list goes on. I looked back on the styles and wholesomeness of prior decades with longing, recognizing a certain superiority in them, but I felt rather helpless in convincing my peers of this. Nor did I really grasp the forces motivating these gradual changes leading us astray. I didn’t know what to blame or how to get at the source of the problems (religion, at this time, actually did not cross my mind). But finally, with my new understanding of time preference, its causes and results, I had a framework I could use to approach these issues.

With this, my view of bitcoin changed dramatically. It was no longer merely a solution to saving for my future, or an opportunity to get rich. I now saw it as an antidote against the progressive corruption of society, and a tool powerful enough to help reverse the damage. I experienced bitcoin’s influence on lowering my own time preference, causing me to improve toward healthier habits. I began to meet other bitcoin enthusiasts who shared the same experience, and we noted that our interests were becoming increasingly aligned in a direction opposite that of the society around us.

I was further convinced of such things when I wrote an article examining the deterioration of beauty in the context of monetary history, which ended up being a significant turning point in my journey. While my secular school environment steered me toward moral relativity and subjective beauty (lying in the eye of the beholder), I now began to question these ideas on a deeper level. In my article, I stumbled into suggesting a tangible metric with which to assess beauty in the works of man. Do the works reflect a low time preference, demonstrating time, talent, effort and care? If so, they inspire these qualities in others, if not, they point society toward vice and nihilism. In this manner I began to feel justified in a more objective view of beauty, which is another concept I had always known deep down, but had previously been challenged in finding the words to explain.

Chapter 4: God and virtue

My article on beauty ended with quote from Antoni Gaudí, a Spanish architect. He designed a cathedral that would take over a century to build, long past his own life. He referenced God when he explained “my client is not in a hurry.” For some inexplicable reason, which perhaps no other person may experience, I became emotional when I read it. I still do. I believe the quote’s significance to me is that it demonstrated a deep caring for the low-time-preference-objective-beauty concept I was empathizing with, and attached it to the devotion of a personified client, God. For me, it was an epiphany about what God can mean to people, in a way I finally understood.

Venerable Antoni Gaudí, 1878

This occurred around the same time I became curious to learn more about God and the Bible for other reasons, in part due to discussions with beloved friends and family members. It was a perfect storm to absorb my attention. I remained skeptical of organized religion, but I now wished to put to trial my closed-mindedness on the topic. I picked up the Bible and began to visit churches of various denominations.

Moreover, I had also been reflecting on the objectivity of the other trancendentals, goodness and truth. Goodness was particularly interesting to me, as it had implications for my behavior and decision making. I had felt like a sufficiently good person, but was that an informed assessment, or just my own naive, self-serving, subjective one? Therefore I began to do a deeper investigation into virtue, vice, and sin. I did not immediately like all that I found—I was quickly implicated, a relatable realization to anyone who has done a similar inspection of any authenticity. Yet if the wisdom of the ages has drawn a sharp connection between the particulars of these virtues and the God that I was now fascinated by if not enamored with, how could I avoid the challenge of conforming my behavior toward this?

“Let him alone. Only pray to the Lord for him: he will himself discover by reading what his error is and how great his impiety.”

— St. Augustine, Confessions 3.12.21

Chapter 5: Philosophy

Also around this time I was following other friendly recommendations to investigate Stoicism. By reading the texts I began to have many other epiphanies about virtue, rational conduct, and what things are important or unimportant in life. I wish I had discovered the wisdom earlier, but I did not, partly because I was distracted by my own folly, and partly because my school system tragically did not teach it. But now I hungered for more of what I was learning. I read several books and listened to many discussions and lectures. I began climbing the Ladder of Love.

“The lovers of learning know that when philosophy gets hold of their soul, it is imprisoned in and clinging to the body, and that it is forced to examine other things through the body as through a cage and not by itself, and that it wallows in every kind of ignorance. Philosophy sees that the worst feature of this imprisonment is that it is due to desires, so that the prisoner himself is contributing to his own incarceration most of all.”

— Plato, Phaedo 82e

I was aware of claims that the Bible contains books not merely of wisdom but divinely inspired wisdom. Not merely ethics but teachings and conduct deemed perfect and sinless. Certainly I was curious, but as a skeptic I also sought to find fault in it. I did find several faults, and there would still be some time before I’d come to realize that the faults I found were not where I thought they were, but in me.

I also found unmistakable wisdom, especially in the Gospels, which were making an impact upon me. I began to take Scripture much more seriously and integrate my understanding of its lessons with my thoughts and writing. It even revealed to me that hunger for wisdom can never be fully satisfied, and true peace must lie elsewhere.

“[Y]et when I applied my mind to know wisdom and knowledge, madness and folly, I learned that this also is a chase after wind. For in much wisdom there is much sorrow; whoever increases knowledge increases grief. […] I saw that wisdom has as much profit over folly as light has over darkness. Wise people have eyes in their heads, but fools walk in darkness. Yet I knew that the same lot befalls both. So I said in my heart, if the fool’s lot is to befall me also, why should I be wise? Where is the profit? And in my heart I decided that this too is vanity.”

— Ecclesiastes 1:17-18; 2:13-15 (NABRE)

Chapter 6: Jesus Christ

“[W]hen I thought of You it was not as of something firm and solid. For my God was not yet You but the error and vain fantasy I held. When I tried to rest my burden upon that, it fell as through emptiness and was once more heavy upon me; and I remained to myself a place of unhappiness, in which I could not abide, yet from which I could not depart.”

— St. Augustine, Confessions 4.7.12

Next I experienced a challenging time of transformation (this one sentence could be expanded into a book of its own, though reading Augustine’s would be a more edifying use of time). It had become necessary.

“If you were blind, you would have no sin; but now you are saying, ‘We see,’ so your sin remains. That servant who knew his master’s will but did not make preparations nor act in accord with his will shall be beaten severely; and the servant who was ignorant of his master’s will but acted in a way deserving of a severe beating shall be beaten only lightly. Much will be required of the person entrusted with much, and still more will be demanded of the person entrusted with more.”

— John 9:41, Luke 12:47-48 (NABRE)

I continued to read and reread the Gospels, and learned more each time I did so. I began to understand the perspective that they contain the greatest story ever written (with bottomless depth), as well as the most profound teachings ever collected. In my naive arrogance I had originally expected the character of Jesus to be like an angelic, fairy tale figure who earned followers with clichés about peace and love, while the more rigorous wisdom would be found among the classical philosophers and stoics. But instead I was surprised to find that the wise truths I was discovering from the latter group actually seemed to pale in comparison to those of Christ, both in density and in perfection. Even the very well-read Thomas Jefferson, who rejected the miracles and divinity of Jesus, recognized something similar:

“[H]is system of morality was the most benevolent and sublime probably that has been ever taught, and consequently more perfect than those of any of the ancient philosophers. [… He was] the most innocent, the most benevolent, and the most eloquent and sublime character that ever has been exhibited to man.”

I think this level of understanding is possible for nearly anyone, even those skeptical of religion, as I was. Loving Jesus as the greatest, most benevolent and wise teacher to ever walk the Earth is an interesting place to arrive at, which can then lead to further questions of the greatest significance.

“He said to them, ‘But who do you say that I am?’” — Matthew 16:15

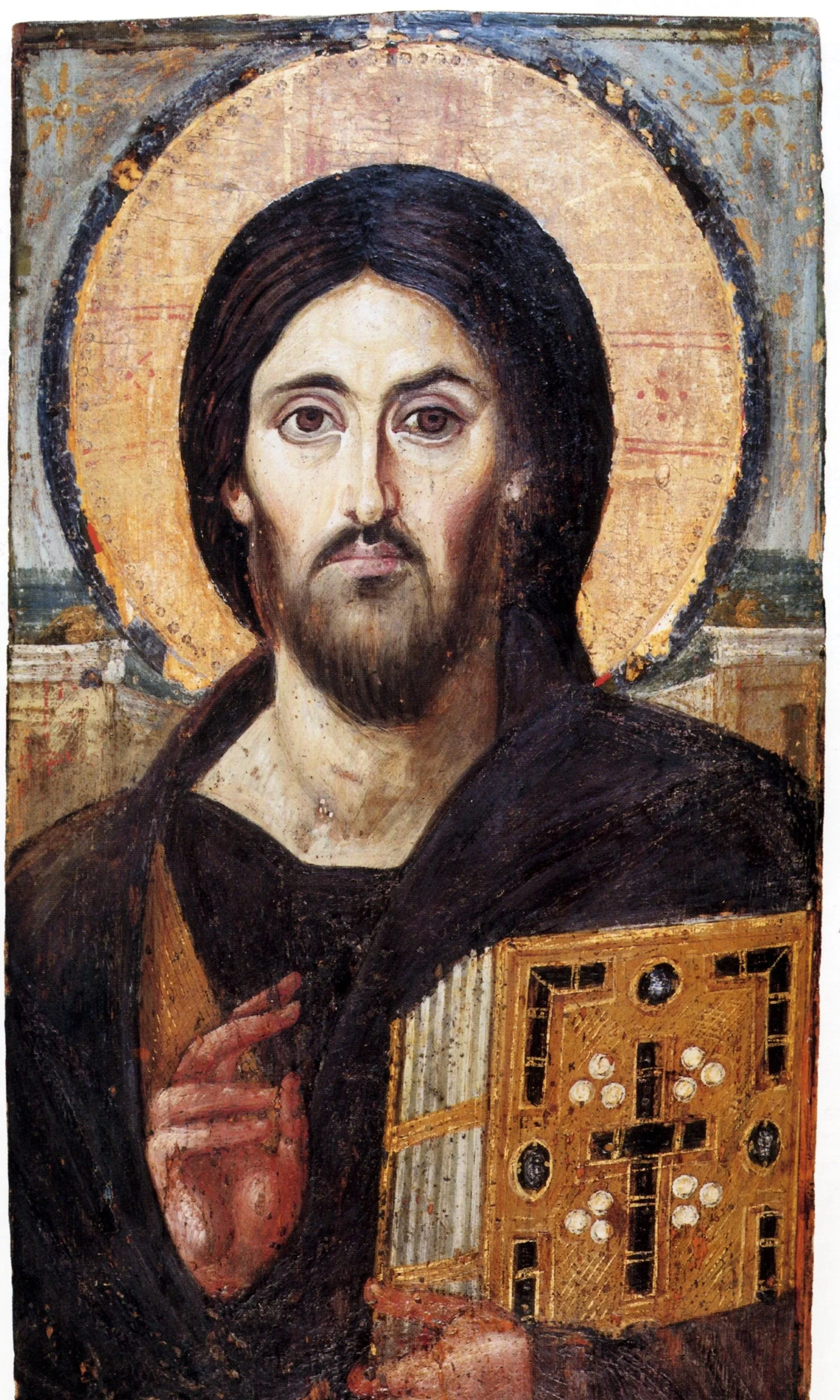

Christ Pantocrator (Sinai), 6th century

“‘Everyone who listens to these words of mine and acts on them will be like a wise man who built his house on rock. The rain fell, the floods came, and the winds blew and buffeted the house. But it did not collapse; it had been set solidly on rock. And everyone who listens to these words of mine but does not act on them will be like a fool who built his house on sand. The rain fell, the floods came, and the winds blew and buffeted the house. And it collapsed and was completely ruined.’ When Jesus finished these words, the crowds were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority, and not as their scribes.”

— Matthew 7:24-29 (NABRE)